Data visualization in a time of pandemic - #3: Mapping the virus

This is a multi-chapter post!

- Chapter 1: Finding reliable data

- Chapter 2: Visualizing exponential growth

- Chapter 3: Mapping the virus

- Chapter 4: We need to talk about flattening the curve

- Chapter 5: On top of the outbreak with daunting dashboards

- Chapter 6: Viral scrollytelling

Chapter 3: Mapping the virus

A pandemic has a strong geographical factor attached to it, so obviously we are drawn to using maps to visualize how the virus is spreading. Both data visualizers and their audience simply love maps, and I personally do to. As a child, my (geographical, historical, biological, even biblical) atlases where my favourite books and I could browse through them for days. However, pretty as they may be, maps have their own pitfalls and caveats. So be prepared!

Beauty in times of despair

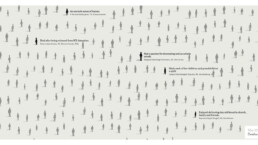

Let’s start with some of the most well-designed examples of maps I have encountered during my research for this chapter. The absolute winner, in my opinion, are these clean but very effective maps by the Washington Post:

Map showing the global spread of the coronavirus on March 27, 2020 (Washington Post).

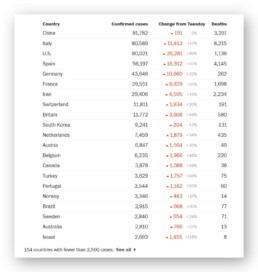

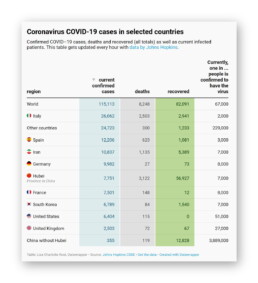

To further clarify things, these maps are complemented by a simple table detailing the exact number of confirmed infections or deaths. This gives the reader the choice to look at the broader picture, dive into the detailed numbers, or both.

Table showing the global spread of the coronavirus on March 27, 2020 (Washington Post).

It should be noted that the BBC uses very similar, equally beautiful maps. These are examples of proportional symbol maps, or what most normal people simply call bubble maps. But why exactly do these bubble maps work so well?

Mapping issues

Countries and territories with confirmed cases on March 10, 2020 (ABC News).

Although somewhat helpful, such a map may say more about how connected a country is to the rest of the world, rather than showing how the virus has spread. In any case, it does not provide information about the number of cases. From this map on March 10, we cannot deduct that there was only one confirmed case in Burkina Faso, but over 10.000 in Italy, and over 80.000 in China.

A typical approach to avoid this issue are choropleth maps, a complicated name for something very simple. Blame the Greeks, choros means ‘region’ and plethos means ‘multitude’, hence the name. My scientific brain always tricks me into saying ‘chloropleth maps’, probably because it thinks about chloroplasts in plant cells. But don’t get your hopes up, there’s no connection at all — just my stupid brain. The ‘chloro-’ in chloroplasts also comes from Greek, but from chloros, ‘green’. The same origin, it turns out, as chlorine (because of its pale green color) or chloroform (which contains chlorine). But my apologies, I digress… I might have been reading too much Stephen Fry lately, who would probably love this kind of etymological exploratory ramblings.

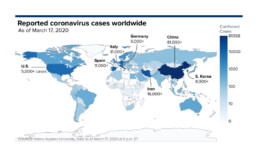

So, a choropleth map. In such a map, regions are again colored, but the value of the color (lightness or darkness) depends on the underlying parameter, for example the number of infections in a country. In its most basic form it looks like this example by CNBC:

Choropleth map of reported coronavirus cases worldwide as of March 17, 2020 (CNBC).

Choropleth map of the spread of the coronavirus in China as of January 26, 2020 (CNN).

However, choropleth maps have their own unfortunate downsides and pitfalls. I will not go into much detail here, as everything was already written down excellently by ‘cartonerd’ Kenneth Field. Let me just summarize:

- choose your colors or color scheme responsibly,

- choose your categories responsibly, and

- use relative numbers to avoid population density distortion.

Or, just maybe, a bar chart might be a better choice:

🎵 The map isn’t the best way to show your data, so the bar chart is where I go. (Source: Kenneth Field)

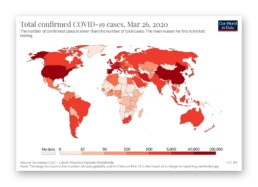

Choropleth map of the total confirmed COVID-19 cases as of March 26, 2020 (Our World in Data)

Bubble maps, such as the ones by the Washington Post shown above, avoid this trap because each nation gets its own bubble, independent of area, population, or population density. This is what makes this kind of chart so successful to map a wide range of values in a wide range of countries around the globe.

There is only one minor downside: bubbles can start overlapping each other when two neighbouring regions have very large values (or one of them has a large value while the other only a small one). Then your bubble chart might start looking like this:

Bubble map on the nCoV-2019 Data Working Group dashboard.

Bubble chart showing confirmed coronavirus cases throughout Europe as of March 27, 2020 (Washington Post)

The return of the table

I already hinted earlier that in some cases, a simple bar chart might be a better option than a complicated map. As Leonardo Da Vinci said: “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication” (except that he never said that). Another simple but effective alternative might just be… a table.

Many great examples can be found, including the Washington Post ones at the beginning of this chapter, but I was particularly charmed by the Datawrapper ones by Lisa Charlotte Rost, with a clever use of color to bring a touch of optimism to this heavy subject matter:

Datawrapper tables by Lisa Charlotte Rost (screenshot: March 18, 2020).

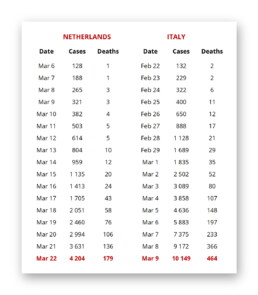

Table comparing the number of infections and deaths between the Netherlands and Italy.

Same data (well, more or less), different story.

Also, differences in age distribution among the population have an impact on the death rate, so it’s rarely a good idea to blindly start comparing different columns or rows with each other, without thinking things through. Remember: if creating panic is your goal, you will always find some data somewhere presented in such a way that you can do so.

There are many, mány more amazing things you can do with tables, also in coronavirus times, but that will be something for another chapter!

Nightmare maps

BBC, by the way, has written an interesting story on an old map showing air travel routes going viral (pun not intended) and causing panic because of poor journalism, such as this badly chosen tweet by the Sun:

Journalism: you’re doing it wrong.

Finally, if you would ever think about using a pie chart as an alternative to a map… just don’t:

I like pies — Pecan pie! Frangipane pie! Key lime pie! — but not this kind, thanks. (Source: European Scientist)

This is a multi-chapter blog post!

Continue reading:

- Chapter 1: Finding reliable data

- Chapter 2: Visualizing exponential growth

- Chapter 3: Mapping the virus

- Chapter 4: We need to talk about flattening the curve

- Chapter 5: On top of the outbreak with daunting dashboards

- Chapter 6: Viral scrollytelling

For all your comments, suggestions, errors, links and additional information, you can contact me at koen@baryon.be or via Twitter at @koen_vde.

Disclaimer: I am not a medical doctor or a virologist. I am a physicist running my own business (Baryon) focused on information design.

Read more:

Data visualization resources: all the links you’ll ever need!

You want to start creating clear and attractive data visuals, but don't know where to start? No worries, here's a complete overview of tools, resources and inspiration you can use as a starting point for your designs.

1 October 2020

Storytelling with Data: Dataviz book review

The Storytelling with Data book has been on my wishlist as long as I can remember, because so many people recommend it as one of the must read dataviz books. So let's see what the fuzz is all about - here's my review!

22 June 2020

Uncommon chart types: Slopegraphs

Slopegraphs appear in 'serious' newspapers, but they are very easy to create yourself. Use them if you want to compare how values have changed between two different points in time!

7 June 2020

Data visualization in a time of pandemic – #6: Viral scrollytelling

In this final chapter, we’ll dive deeper into some of the insightful stories which have been published about the novel coronavirus and the COVID-19 pandemic. Rather than looking at single charts, we’ll highlight some long-form stories about the origin of the virus, how it works, and how it spread.

3 June 2020

Five steps towards improving your dashboard

Today I would like to share with you the five steps I usually follow when I analyze and improve dashboards. If you are planning to analyze and improve your own dashboard, or maybe the dashboard someone else created and you want to provide feedback on, you could follow these five steps as well.

18 May 2020

Dear Data: Dataviz book review

Last February, on a cold and rainy day, I received the Dear Data book as part of a Dataviz Drawing workshop by Stefanie Posavec. A pretty large and heavy book, the kind you could put on your coffee table to show off (which I did!). Let's review it!

3 May 2020

We are really into visual communication!

Every now and then we send out a newsletter with latest work, handpicked inspirational infographics, must-read blog posts, upcoming dates for workshops and presentations, and links to useful tools and tips. Leave your email address here and we’ll add you to our mailing list of awesome people!